Panjabi Wrestling is a project set up and run by educational charity digital:works.

A group of 12 young people have lead this project exploring the history of Panjabi Wrestling, known as Pehlwani.

They have undertaken research with an historian of the sport, taken part in workshops to understand the role of the sport in Panjabi heritage, culture and religion and also how it arrived in the UK with the diaspora who came from India and Pakistan from the 1950s. They have worked with a wrestling coach from Slough Wrestling Club to learn the actual skills of wrestling that are currently being lost.

The group have learnt oral history and film making skills from digital:works and conducted interviews with older members of the UK based Panjabi community to explore and record the history of the sport. The interviews have also be edited to create an informative oral history based documentary.

This project website and blog has been developed as the project progressed and houses the full interviews. The edited film also appears here. Resources generated are being given to archives.

A launch event was presented by the young people to an audience followed by a Q&A and discussion in January 2019.

We are grateful to the Heritage Lottery Fund and Slough Wrestling Club for financially supporting this project.

digital:works has been running oral history projects across London working with communities to explore the history of work and workers in the capital. Projects so far include printers on Fleet Street, bus workers, underground workers, black cab drivers, jewellers in Hatton Garden, tailors in Saville Row, the Thames Lightermen, Thames boatyards and more. Other projects explore the history of Battersea, North Kensington, Southall, Eel Pie Island, as well as some of London’s indoor and street markets. If you would like to see any of these wonderful films and find out more about digital:works please visit:

www.digital-works.co.uk.

Pahelwani, or ‘Kushti’ as it is also known, is the traditional wrestling of Punjab, the ‘Land of Five Rivers’. It is believed to be one of the oldest martial arts in existence.

It is a synthesis of an indigenous Hindu form of wrestling called ‘Mal-yudh’, the ancient discipline of Yoga, and a Persian form of wrestling brought into the Indian subcontinent through the gateway of Punjab by the Indo-Persian and Mughal dynasties.

The classical texts bear eloquent testimony to the popularity of wrestling since ancient times. Of the more memorable fights mentioned are the bout between Bhim and Jarasandh narrated in the Mahabharat, the contest between King Bali and the mighty King Ravan of Lanka in the Ramayan, and the duel between Rustum and Sohrab described in the Persian epic, the Shahnama (‘Book of Kings’).

A practitioner of Pahelwani is called a ‘pahelwan’. This term is derived from the Persian ‘pahlavan’, which means champion or warrior. It was particularly used to denote those warriors who excelled on the battlefield. The greatest pahlavan recorded in the annals of the Persian tradition was the legendary warrior-king, Rustum. Until modern times, champion pahelwans in India were honoured with the title ‘Rustum-i-Hind’ (Rustum of India).

For centuries, the wrestling lifestyle has enshrined the essence of man. In the confines of the carefully prepared earth wrestling pit (‘akhara’) and under the expert guidance of Pahelwani masters, variously called ‘guru’ or ‘ustad’, the pahelwan achieved self-discipline through physical fitness, as well as identity and purity of the body, mind and spirit.

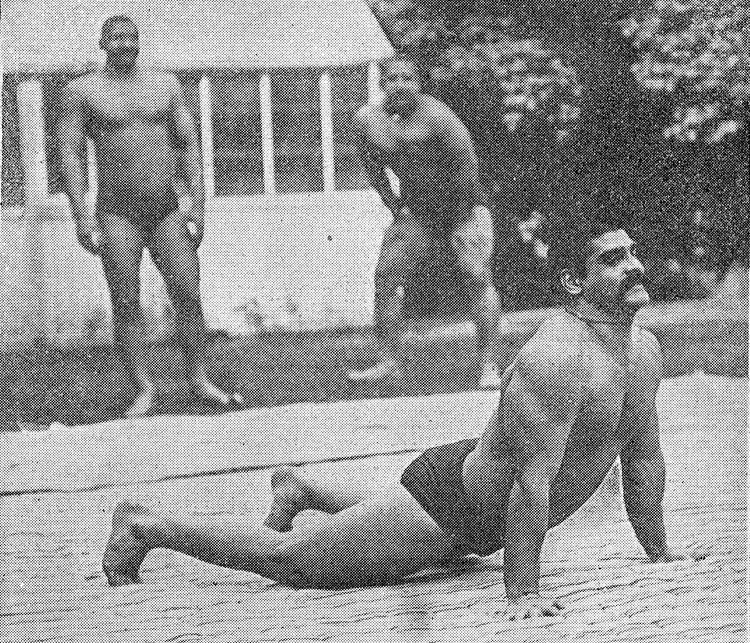

The art of Pahelwani is comprised of stance (‘paintra’), and moves and countermoves (‘daw-pech’).

Paintra is the art of standing in the akhara. It is the point of entry into the act of wrestling and the prelude to every competitive wrestling bout (‘dangal’). It is the fixing of the feet on the ground after having made a move or having countered an attack. A pahelwan’s stance puts him in a position to attack or retreat.

Although stance is of pre-eminent importance, the art of Pahelwani also entails the careful execution of the hundreds of moves and countermoves called daw-pech, a litany of feints and parries.

A skilled pahelwan’s objective is to achieve an economy of effective motion. From his perspective, every single move, glance, shift of weight and moment of motionlessness ought to be classifiable into some aspect of a paintra or daw-pech. He must also be able to read ahead and anticipate his opponent’s moves by examining the geometry of his stance. Because every move can be answered with a whole range of countermoves, no two bouts are ever the same. No move is predictable or established as inevitable given the configuration of previous moves; structured improvisation is the key.

Pahelwans are taught moves and how to put moves together in chains of motion, but it is only through practice that the most expert learn the art of improvisation. An accomplished pahelwan is capable of reading the pure grammar of movement most clearly, and is able to take advantage of his opponent’s misreading or his carelessness. He can interrupt a movement to his advantage and translate it into something for which it was not intended.

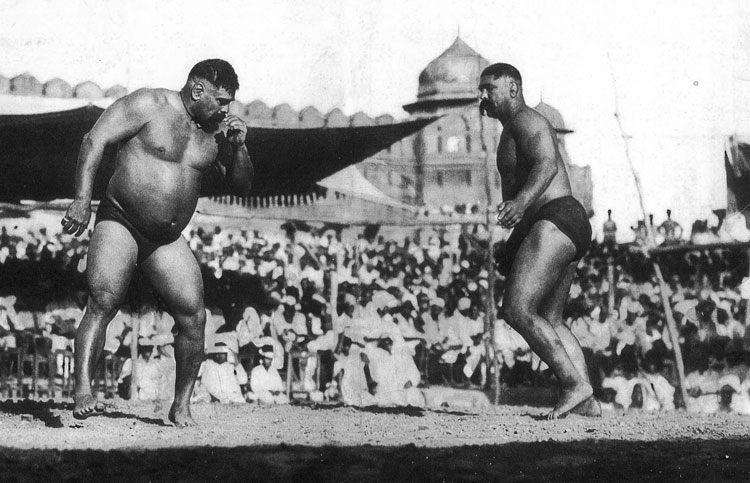

In their day, champion pahelwans were devastating because they trained hard, ate big and possessed superior technique, power and fighting hearts.

Many of the best professional pahelwans were born into wrestling families; a son followed in the footsteps of his father and started to wrestle as soon as he was able to walk. As Pahelwani was the child’s one and only pursuit, and as he learnt young and kept his body supple under good teachers, who were to be found in great numbers, the akhara system produced extraordinarily efficient and scientific wrestlers.

The pahelwan, though very much a part of society, considered himself a man apart. When he entered the akhara, he left behind him the mundane for a world of tranquillity and authority. He would adhere strictly to the moral principles of continence, honesty, internal and external cleanliness, simplicity, and contemplation of the Divine, an attribute that he shared with the ascetic fakir or sadhu of the Muslim and Hindu worlds respectively.

The diligent pahelwan strove towards the ideal of perfect health. To achieve this he had to release himself from the world. In this perfect state of self-realization (‘jivanmukti’), ignorance was banished as spiritual consciousness and wisdom developed. At this level, a pahelwan was unaffected by emotions of any sort; he had no concern with the sensory world of pain and pleasure, suffering and greed.

Central to the development of a pahelwan’s moral and ideological framework was physical training (‘virayam’), the focal point of his daily routine. This entailed the repetition of specific exercises and the continual practice in actual wrestling.

Stress was placed on stamina and strength rather than beauty. If a pahelwan became a very large man he was given additional exercises to improve stamina and to harden his body. For instance, he was made to turn the shaft of the Persian wheel (the traditional device used to draw water from wells), a task usually performed by a couple of bullocks or camels. This type of exercise done for a length of time was prodigious hard work.

by Parmjit Singh, Kashi House

We would like to thank Kashi House for all their help and support on this project.

Kashi House is a not-for-profit company dedicated to producing high-quality books on the rich cultural heritage of the Sikhs and Punjab. You can find out more here.